Polio basics

Even though you might think that polioviruses are gone because you might not hear much about them, they still pose a very real threat in a few parts of the world and they could return to wider circulation if we do not eradicate them.

What are polioviruses?

What do polioviruses do to people?

What tools do we use to protect ourselves from polioviruses?

What is happening with respect to global polio eradication?

What are the similarities and differences between polio eradication and smallpox eradication?

What can you do to help eradicate polio?

Common abbreviations

What are polioviruses? (get more information about this from the World Health Organization and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

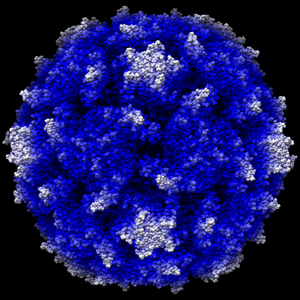

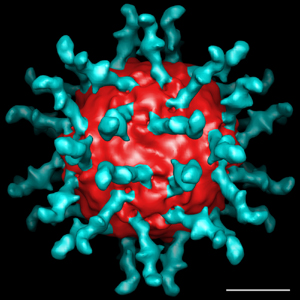

- Polioviruses belong to the virus subgroup known as enteroviruses and specifically to the family Picornaviridae. Enteroviruses are small ribonucleic acid (RNA) viruses that remain stable in and survive under acidic conditions. After ingestion, enteroviruses may inhabit and reproduce in the throat and gut. Images of polioviruses show the three-dimensional structure of the virus and the receptor bound to the virus.

Three-dimensional structure of poliovirus at 2.9 Å resolution. Hogle, JM, M Chow, and DJ Filman. Science 1985; 229:1358-1365. Shown with permission from Professor J. Hogle. |

Three-dimensional structure of poliovirus receptor bound to poliovirus. Belnap, DM, BMJ McDermott, DJ Filman, N Cheng, BL Trus, HJ Zuccola, VR Racaniello, JM Hogle, and AC Steven. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2000;97:73-78. Shown with permission from Professor DM Belnap. |

- Three serotypes of poliovirus exist (Types 1, 2 and 3, also called P1, P2, P3) and they can circulate independently. The three types differ enough that infection with one type does not prevent infection with another type and immunity to one type does not yield significant immunity to the others. Type 1 and 3 wild polioviruses still endemically circulate in parts of 4 countries (Afghanistan, India, Nigeria, and Pakistan), but eradication of wild poliovirus type 2 occurred in 1999.

- Humans are the only reservoir that can sustain poliovirus transmission.

Transmission typically involves fecal to oral spread, but oral to oral spread

may also occur.

Back to questions

- Most poliovirus infections do not lead to symptoms, but in susceptible people (i.e., people not yet immune to the virus) approximately 1 in 200 infections result in paralytic poliomyelitis (or paralytic polio). After entering the central nervous system, poliovirus may replicate in and destroy motor neurons, which may manifest clinically as paralyzed limbs, respiratory arrest, and in rare cases as deaths.

- You can become immune through recovery from natural infection or vaccination. Immunity protects people from getting the disease and developing paralytic polio. However, immune people can become asymptomatically infected and participate in the transmission of virus (although the chances of becoming infected and passing the virus on to others is lower for immune people than for people who are fully susceptible).

- Prior to the widespread use of poliovirus vaccinations, paralytic polio led to thousands of cases of paralysis annually in the U.S., with more than 21,000 paralytic polio cases, including more than 3,000 deaths, reported in the U.S. in 1952. In the late 1980s, estimates suggested that polio paralyzed approximately 250,000 per year globally.

- In addition to the actual effects of paralysis and death, prior to vaccination polio also terrified people and incited a large amount of fear. Polio outbreaks devastated some American families and communities in the early- and mid-1900s. The image of children in iron lungs (devices used to breath for a polio victim with lung muscle paralysis) provides a powerful reminder of the toll that polio once took in the U.S.

- The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) provides numerous images of how polio impacts people around the world as well as images captured as part of the polio eradication campaign. This includes a photo of the person with the last known cases of polio in the Americas (in Peru, 1991). Rotary International, one of the GPEI spearheading partners, produced a report that includes photos of the last known cases of polio in 3 of the 6 WHO regions. Back to questions

|

|

What tools do we use to protect ourselves from polioviruses?

- Two vaccines exist that provide protection against polio disease. The GPEI has relied exclusively on the inexpensive and easily administered live, oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV), which has demonstrated the ability to prevent poliovirus transmission even in the most difficult settings. However, as a live, attenuated poliovirus, OPV can in very rare cases mutate towards a form that can cause paralytic polio (known as vaccine-associated paralytic polio or VAPP). In populations with low coverage levels of OPV, the live virus strains can in some cases circulate sufficiently and cause outbreaks of circulating vaccine-derived polio viruses (cVDPVs).

- Most industrialized countries currently use the injectible, inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV), which provides excellent but relatively expensive individual protection against polio disease. Limited research currently leads to questions about the ability of IPV immunity against infections to prevent poliovirus transmission in developing countries.

- Currently, no antiviral agents exist to treat or control poliovirus infections, although a recent report by the National Research Council recommended development of at least one polio antiviral drug to enhance the set of tools currently available for the control of poliomyelitis outbreaks.

- Get more information about poliovirus vaccines from the

World Health Organization and the U.S.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Back to questions

What is happening with respect to global polio eradication? (quoted and paraphrased from Thompson KM. Poliomyelitis and the role of risk analysis in global infectious disease policy and management. Risk Analysis 2006;26(6):1419-1421).

In 1988 estimates of the annual number of cases of paralytic polio were approximately 250,000 and wild polioviruses were circulating in over 125 countries. Given this large

burden and demonstrated successful elimination of wild polioviruses in the Americas,

the World Health Assembly committed to global eradication of wild polioviruses

by the year 2000. Although the goal of eradication has yet to be achieved, the

Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) has made remarkable progress and

reduced the number of cases of paralytic polio to fewer than 2,000 cases per

year (with endemic circulation remaining in only Afghanistan, Nigeria, Pakistan,

and northern India). Challenges in these remaining endemic areas differ: vaccine

campaigns in India continue to miss children (particularly in minority populations),

campaigns in Nigeria suffer from operational and political issues, and campaigns

in Afghanistan and Pakistan are limited by security issues associated with current

conflicts. In addition, during the past several years, the challenges to successfully

eradicating wild polioviruses and our knowledge of them increased as new risks

emerged. Notably, as some polio-free countries reduced or eliminated their use

of live oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV), local outbreaks occurred due to neurovirulent

circulating vaccine-derived polioviruses (cVDPVs). These experiences reveal

that OPV circulating through populations with enough susceptible individuals

can mutate back toward wild poliovirus and cause paralysis. Consequently, eradicating

virulent polioviruses will eventually require stopping the use of OPV, which

is currently the vaccine of choice for the GPEI due to its low cost, population

immunity benefits, and ease of administration. Thus, the GPEI and national health

leaders now confront the challenge of encouraging high coverage with OPV to

finish the job of eradication and increase population immunity prior to OPV

cessation, while at the same time they must begin plans for coordinated OPV

cessation and pursue eradication in the context of numerous competing opportunities

for scarce health resources. Adding more complexity, modern technology now supports

the ability to synthesize poliovirus in a laboratory, a demonstrated reality

recognized not long after the events of 9/11 altered perceptions about the potential

risks of intentional events (at least for some individuals and countries). Finally,

the existence of a small number of immunodeficient individuals who continue

to excrete polioviruses they did not clear after receiving OPV raises the possibility

of these viruses (called iVDPVs) potentially infecting susceptible individuals.

Incidental discovery of just such a virus from an unidentified source in an

asymptomatic child in Minnesota recently raised awareness of this risk. Given

these challenges, the GPEI is working to interrupt all remaining chains of transmission

as quickly as possible and is starting to plan to manage the risks of polioviruses

following the complete and sustained interruption of circulating wild polioviruses.

The GPEI provides current case

counts and maps.

Back to questions

What are the similarities and differences between polio eradication and other eradication campaigns?

- Smallpox is the only disease successfully eradicated to date and countries stopped routine smallpox vaccination around the time of its global eradication in 1980. Smallpox and polio eradication are similar because humans represent the only known disease reservoirs capable of sustaining transmission, viruses cause both diseases, and vaccines exist that make eradication possible. Infection with the variola virus always causes very distinct clinical symptoms of smallpox. This made it relatively easy to find the last reservoirs of variola virus and to effectively use vaccines to wipe out smallpox. In contrast, most poliovirus infections are asymptomatic, which makes it more difficult for public health authorities to locate the virus and which necessitates the use of current laboratory diagnostic capabilities and support of a global polio laboratory network. Comparisons of the economics of smallpox and polio eradication efforts warrant caution given the relatively different starting points. By the time smallpox eradication began, smallpox had been eliminated in all by 31 countries, with fewer than 1 billion people living in endemic areas. In contrast, when polio eradication began in 1988, polio was endemic in over 125 countries, with over 4.5 billion people living in endemic areas. In addition to the much larger population, global transit increased dramatically.

- Yaws eradication represents another interesting campaign for comparison.

Following a 95% reduction in cases of Yaws that resulted from eradication

efforts, the Yaws eradication activities were "integrated

into the primary health care system to deal with the 'last cases.' Resources,

attention and commitment for yaws activities gradually disappeared."

Resurgence of Yaws led to a recommitment to global control efforts, and although

Yaws eradication still appears possible no global commitment to eradication

currently exists.

The GPEI currently faces similar calls to shift the goal away from polio eradication

to control and demands to integrate the resources for polio eradication into

the global health system.

Back to questions

What can you do to help eradicate polio?

- Support polio vaccination

- Support the GPEI

Back to questions

Used generally by polio researchers and policy makers:

AFP = acute flaccid paralysis

aVDPV = ambiguous vaccine-derived poliovirus

cVDPV = circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus

CDC = U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

eIPV = enhanced-potency inactivated poliovirus vaccine

GPEI = Global Polio Eradication Initiative

IPV = inactivated poliovirus vaccine

iVDPV = vaccine-derived poliovirus from an immunodeficient individual

mOPV = monovalent oral poliovirus vaccine

NIDs = national immunization days

OPV = oral poliovirus vaccine (generally trivalent unless otherwise specified)

SIAs = supplemental immunization activities

SNIDs or sNIDS = sub-national immunization days

tOPV = trivalent oral poliovirus vaccine

VAPP = vaccine-associated paralytic polio

VDPV = vaccine-derived poliovirus

VP1, VP2, VP3 = viral protein 1, 2, and 3, respectively

WHA = World Health Assembly

WHO = World Health Organization

WPV1, WPV2, WVP3 = wild poliovirus type 1, 2, and 3, respectively

Used in our modeling:

HIGH = high-income country

LMI = lower middle-income country

LOW = low-income country

MPI = maximum population immunity scenario

RPI = realistic population immunity scenario

TIAs = targeted immunization activities

UMI = upper middle-income country

Back to questions

http://www.kidsrisk.harvard.edu/polioinfo.html